By Megan Nemire

It took almost three weeks on this trip to Cambodia, but I became sick. Maybe I ate something questionable, or assumed safety in a glass of ice tainted with bacteria my Western body system cannot process. However it happened, I was incapacitated for a day, traveling only to the restroom and bed, as well as the recesses of my fearful feelings I hadn’t acknowledged previously.

Though it was clearly a physical reaction, my body’s natural response fighting something foreign or dangerous, I became quite curious about the relevance of this timely… (how do I say it politely…) purging of the system.

I had taken in a lot over the past three weeks. We all had. Our clients and many strangers we passed on the streets had experienced the depths of human experience. Trauma. Domestic abuse. Sexual exploitation. Aftermath of genocide and political upheaval. So which of the many hardships was too much for me to digest?

Oh yes. I had finished reading Never Fall Down (2012) the day before the sharp pains seized my stomach. In this book, McCormick tells the story of Arn Chorn Pond‘s life*, a haunting journey through the terrors of the extremist group, the Khmer Rouge, led in shadow by Pol Pot. The following provides historical context according to the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center (2004) and McCormick et al. Writing this section helped me address my deep need to make a shred of sense about something truly incomprehensible. Liking clarity for myself, at first I wondered if this was the coping strategy of intellectualization, using thought to override anxiety of emotion (Vaillant, 1977). However, no. I am attempting to align the cognitive with the emotional. I want to understand at least a sense of why these atrocities took place. I wanted to know the Khmer Rouge’s goals when waging this genocide. This historical piece is a practice of acceptance. It also provides essential context for the personal sharing afterward, about my experience walking through the Killing Fields.

The Khmer Rouge Genocide

On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge, a group of peasants throughout the country of Cambodia, intentionally selected for their status as “base people” or working class, seized all of the major cities and marched the people out. Led by Pol Pot who mostly hid safely in Thailand, the Khmer Rouge was created as a group of former teachers, many influenced by the French Communist party. They were people who were themselves educated, and with social privilege.

Under the guise of evacuating homes to escape attacks from the Americans or Vietnamese, and with threat of immediate death by gunshot or bayonet slashing from these black-cloaked Khmer Rouge soldiers, the people of the cities gathered their essential belongings and marched out into the countryside. There were hundreds of thousands of people in the crowds, many starving and dying along the way, every step forward was given the promise of care from Angka, a new word to them at the time, which means, the organization.

Those that were forced to march were the educated people, those with land or wealth, they were the artists, musicians, teachers, doctors, anyone with special training. I began to consider the psychology of cutting off shadow parts—educated people leading the uneducated to kill the educated. Deep breath, and I continue my descent into history. The Khmer Rouge was guided by “four interrelated principles: (1) total independence and self-reliance, (2) preservation of the dictatorship of the proletariat, (3) total and immediate economic revolution, and (4) complete transformation of Khmer social values.” (Choeung Ek Genocidal Center, 2004). They set out to “rusticate the cities”, to return Cambodia to a completely agrarian society, to strip away the classes and restore ‘equality’ to the people. They prohibited money, the free market, religion, education, and anything that contested their mission. Schools, churches, temples, and hospitals were shut down, and changed into prisons, granaries, and “reeducation camps”.

My stomach surges as I type, because the truth of the history fades to darkness. The people were forced into labor of growing rice on overworked soil, tasked with impossible yield goals. Many died as they worked. Many were killed mercilessly, accused of being traitors, pit against their family members and forced between condemning themself or their brother to death. Some went to the prisons, where they were tortured. Those that survived were sent to the killing fields, where they were murdered, and buried in mass graves. Families were separated into work camps for men, women, and children. Growing rice all day and night, many died from exhaustion, starvation, disease, and broken hearts. The Khmer Rouge continually restricted their criteria to let a person live, and many of the soldiers ordered to murder others were then killed themselves, declared as traitors.

It is estimated that 2 to 3 million people were murdered during the Khmer Rouge regime, approximately 30% of the Khmer population. They were murdered by their own people.

It is important– actually, essential– to acknowledge, to discuss, to let the heart break even if for a moment when reading these truths. Choeung Ek’s mission of education and sharing what happened is held in hopes that if we talk about these horrors, we can prevent them from repeating. Or at least we can try. Perhaps, dear reader, you might take a moment of silence in honor the souls whose lives were taken during this time.

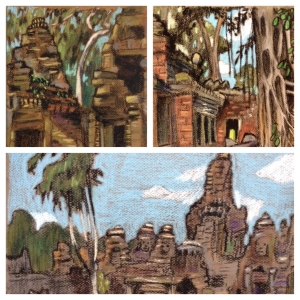

“A little life amongst the death”

Response art, Megan Nemire

I have yet to find a way to honor and submit to the horror of these truths. And it seems, this lack of ability to cope with genocide and murder is quite a natural response. For me, reading a personal account of one man’s survival in a terrifying time built up in my gut like a strain of mutated human genetics. It was too much for my system to handle. So I vomited it up, let it all pour out. My body was rebelling against the truth.

Yet, after that day of somatic release, my system regulated enough for me to stand up again. My stomach restored a working balance, while still carrying a dull pain, and the moments of relief extended. My own was a parallel process of what I had read, only I was given the time and space to heal. The children I read about, children that Arn Chorn Pond knew during his own life, would have been taken for their ‘rest’ by death in a pile of bodies in a mango grove. This realization was horrifying and humbling. Since I get to live, I have the responsibility to share their story.

Visiting Choeung Ek Genocidal Center

Carrying a coconut for hydration and a stash of Cipro and bread, I walked the next day through the Choeung Ek Genocidal Center, just outside of the large, busy city of Phnom Penh. This was one of at least 300 killing fields across the country, and is now an area of remembrance, education, and honoring.

The van ride there was stirring to me, realizing the close proximity of this field of death, barely outside a city that is once again sprawling. At that time, it was a ghost town, completely evacuated.

Photo by Megan Nemire

Though I am a person who feels very deeply all across the emotional spectrum, and ordinarily expresses herself with conviction and passion, this morning I found myself silent. I heard Arn’s words, you feel, you die. You cry only in your mind. This is how he survived.

So I walked the sites, which without marking might appear as any ordinary field, with clusters of trees, a small lake, and small mounds of dirt that stir the ground. I stood in silence at the mass graves. Bowed in reverence at the piles of bones and torn cloth. Listened to the audio player given from the staff that shares personal stories of struggle from survivors. All along I heard the words, and the feelings made themselves known, but they were trapped somewhere within myself.

Photo by Megan Nemire

At the end of walking my lap around the lake, I approached a tree covered in bracelets of all colors, hanging from the bark. The sign read both in Khmer and English, “Killing tree against which executioners beat children”. Deep sigh and my stomach drops yet again. This tree had been used as a death machine for women and children, its own sturdy nature twisted into a weapon cheaper than bullets. They were smashed into its trunk, head first.

I stood close to this tree, oscillating my attention between inward and outward focus. I was sensing what was there. There was my own profound sadness, still trapped behind a wall; there was my disbelief, fear, horror, relentless questioning, and futile need to make sense of this atrocity. However, I didn’t sense that trapped feeling outside of myself. It occurred to me that perhaps, in this place of reverence where bones and clothing are moved to a stupa, and honored in a Khmer death ritual, that the spirits of those who died here have left this land.

Standing close to the trunk of the tree, the bark that stayed firm against broken skulls, I looked up. There were leaves. This tree, sentenced as the tool for taking hundreds of innocent lives, was still growing itself.

I had a moment of outrage, on behalf of the tree, for being transformed into a killer. I quickly found my outrage to be misplaced. My outrage was for the people, for the thousands that died at Choeung Ek, the two or three million people killed in the Khmer Rouge genocide, for the young Khmer men and women used as disposable soldiers, made to execute their own people through brainwashing, lies, and threats of their own death.

The outrage led to sadness, the sadness to hopelessness. Hopelessness to a series of deep breaths. There is horror in the world, and I am still here, standing. There can be death and life within the same being. A tree can murder and grow. A country can destroy itself, and its people can still heal. A person like me can witness, fall apart, break down, and keep walking, keep writing, keep feeling, keep honoring.

Photo by Megan Nemire

One man I met here implored me, “Thank you for visiting my home. When you go back to yours, tell people about us. Tell people about Cambodia.” For today, I have told you about these deaths. And soon, I will tell you about the life.

Please note that while individual members have varying views on topics discussed in our blog, NCAS-I as a whole honors multiple perspectives, within respectful reason, and does not aim to censor material shared in our blog writings. So please keep this in mind while reading our blogs. And please feel free to add your perspective too.

Author/artist note: Please do not use the images without permission. Thank you.

*Stay tuned for a blog post from Krystel in a couple days, sharing more about Arn Chorn Pond’s life, and our experience meeting him.

References

McCormick, P. (2012). Never fall down. New York: Harper Collins.

Unknown author. (2004). The Killing Fields Museum – Learn from Cambodia. Retrieved from: http://www.killingfieldsmuseum.com/genocide1.html

Vaillant, George E. (1977). Adaptation to life. Boston: Little, Brown.